Originally published on yarno.com.au

Was it the Greeks or the Spartans who won the first Peloponnesian war? What was it that Hamlet was worried about? That his step-dad wasn’t spending enough time with him? And how do you do long-division? Is it something to do with fractions??

These are all things that were taught during Year 12, and which at some point, I knew. They seem, however, to have slipped from my brain. History, English, Maths: they ruled my life for twelve horrible years. And yet, my grasp on them now is at best, limited. Especially when it comes to Maths – if I’m honest I struggled the whole way through General Maths and only ever vaguely understood anything after they started adding letters into the mix.

The reason I don’t know any of this anymore (even though Mum, Dad I studied so hard, ten hours a day) is because I haven’t gone over it at all since I sat my final HSC exam. I don’t think I’ve even thought about Hamlet since.

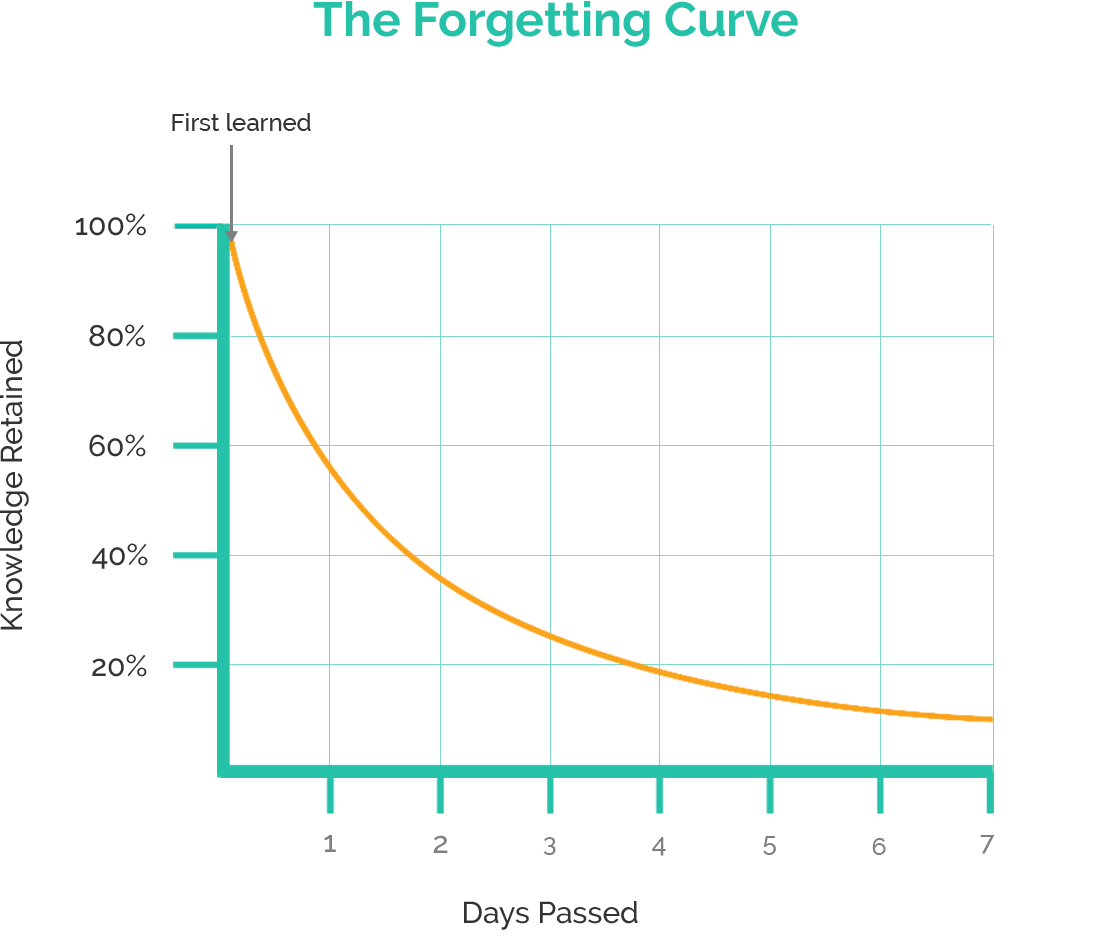

This is a universal experience. Everyone forgets the things they learned. You can actually plot the rate at which you forget things, and when you do it forms a graph called the “Forgetting Curve”. This curve and the phenomenon of forgetting was first discovered and studied by this fella down here:

The Forgetting Curve

His name is Hermann Ebbinghaus. He was a German psychologist who, besides growing a beard that looks exactly like an upside-down spade, spent his time studying learning and memory retention. He conducted a series of experiments where he would write down a bunch of random syllables like this:

XBH, AOJ, APK, AJI, AOI

Then he would repeat them to himself until he had them completely memorised. Once he had them down pat, he would attempt to recall that series of syllables at periodic intervals; after a day, after two, then a week, a month, even six weeks after first learning them. After each attempt to recall them, he recorded exactly how many of the syllables he could summon in the correct order, and plotted them on a graph. That graph looked something like this:

What do Ebbinghaus’ findings mean?

Basically, what Ebbinghaus found is that our brain is like a leaky bucket. If, at the time of first learning something you know 100% of that content, a day later it all drains out of your head and now you only know about 50% of that same content. It keeps going exponentially – after a couple days you’ll only remember 30-40%. Your brain keeps draining and draining until it reaches a plateau about a month later. At this point you probably only remember about 20% of what you actually learnt. Useless brain! This is why I can vaguely remember that Pericles was an important General in 5th BCE Greece, but I can’t remember anything he actually did.

What Does This Mean for Long-Term Learning?

This means exactly what we all know – cramming might help you pass the test, but it won’t give you long-term results. I can’t remember anything about Hamlet because I haven’t read it since I had class with Mrs…what was her name? Wow, I literally haven’t thought about year 12 English in so long that I can’t even remember my teacher’s name. No wonder I can’t remember if Ophelia was Hamlet’s girlfriend or his sister.

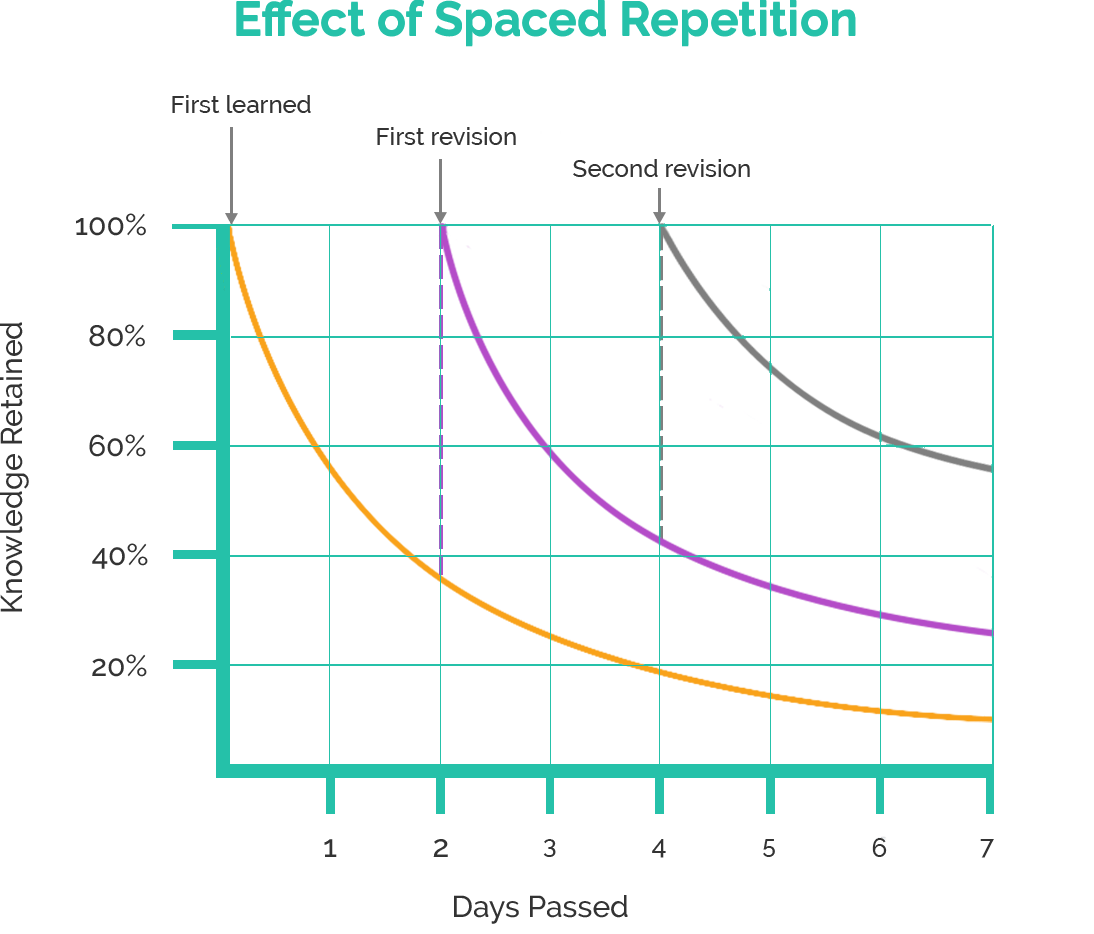

There’s a way to fix this however, and it’s exactly what CyberBite is built around – spaced repetition. If you revise something a day, a week, even a month after you first learn it, it strengthens the memory in your mind, and makes the forgetting curve much more gradual. It starts looking more like this:

This is why I can remember my entire credit card number (including expiry dates and CVV) but can’t remember how to do long division. Besides acquiring a mild-to-moderate online shopping addiction, I’ve been practising spaced repetition with that number for nearly five years. In contrast, I haven’t thought about long division since I was 17 and the only thing I still remember about it is that it’s hard.

So we’ve got good and bad news: the bad is that it takes more than one exam fuelled by 13 coffees, an elevated heart rate and the whole year’s worth of content to truly know something. The good is that you don’t need to put yourself through that terrible experience to learn and understand. If you learn gradually, and go over what you’ve learnt, not only will it yield long-term results, it might even make the experience bearable.